- News

- India News

- Anti-graft Act covers all pvt bank staff too: SC

Trending

This story is from February 24, 2016

Anti-graft Act covers all pvt bank staff too: SC

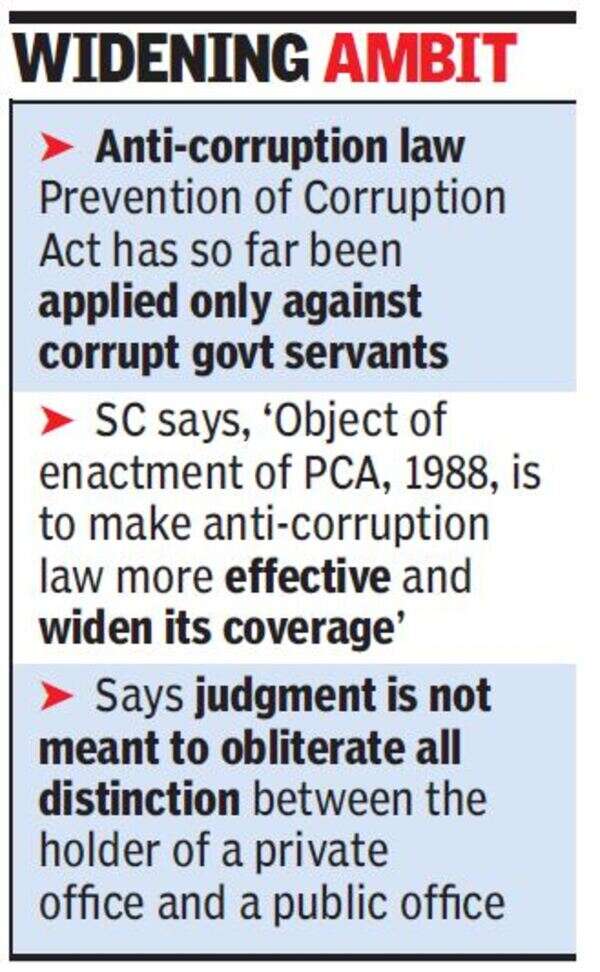

In a significant judgment expanding the scope of the Prevention of Corruption Act, the Supreme Court on Tuesday brought all private bank employees within the ambit of the anti-graft law, which had so far been applied only against corrupt government officials.

NEW DELHI: In a significant judgment expanding the scope of the Prevention of Corruption Act, the Supreme Court on Tuesday brought all private bank employees within the ambit of the anti-graft law, which had so far been applied only against corrupt government officials.

A bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi and Prafulla C Pant, in separate yet concurrent judgments, overturned a Bombay high court verdict endorsing a trial court decision that cognisance of PC Act charges could not be taken against ex-chief Ramesh Gelli and ex-MD Sridhar Subasri of the erstwhile Global Trust Bank (GTB) in a Rs 41-crore corruption case because they were not public servants.

This was before GTB merged with Oriental Bank of Commerce (OBC) in 2004.

The CBI had lodged an FIR against Gelli and Subasri based on a complaint filed by the OBC’s chief vigilance officer. The charges of corruption and siphoning off Rs 41 crore date back to the time when GTB operated as a private bank.

“It is clear that object of enactment of Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 was to make the anti-corruption law more effective and widen its coverage,” he said.

Agreeing with Justice Pant’s conclusion that Gelli and Subasri should be prosecuted under PC Act as well, Justice Gogoi said, “In a situation where the legislative intent behind enactment of PC Act was to expand the definition of public servant, the omission to incorporate the relevant provisions of PC Act in Section 46A of the Banking Regulation Act can be construed to be wholly unintended legislative omission which the court can fill up by a process of interpretation.”

In doing this inclusive interpretation, Justice Gogoi said he was aware of the principle that what had not been provided for in the statute could not be inserted by the courts.

“Enactment of PC Act with the clear intent to widen the definition of ‘public servant’ cannot be allowed to have the opposite effect by expressing judicial helplessness to rectify or fill up what is a clear omission in Section 46A of the Banking Regulation Act,” he said. However, Justice Gogoi clarified that the judgment was not meant to obliterate all distinction between the holder of a private office and a public office.

“It will be more reasonable to understand the expression ‘public servant’ by reference to the office and the duties performed in connection therewith to be of a public character,” he said.

Before the amendment to Section 46A of Banking Regulation Act in 1994, only the chairman, director and auditor of a bank were regarded as public servants in connection with offences under IPC. But the amendment brought within its purview chairman appointed on a whole-time basis, managing director, director, auditor, liquidator, manager and any other employee of a banking company, terming them as public servants for offences under IPC.

The court ruled that if they were public servants in connection with offences under IPC, they would be deemed to be so under Prevention of Corruption Act as well.

“The unequivocal legislative intent to widen the definition of ‘public servant’ by enacting PC Act cannot be allowed to be defeated by interpreting and understanding the omission in Section 46A of the BR Act to be incapable of being filled up by the court,” Justice Gogoi said.

A bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi and Prafulla C Pant, in separate yet concurrent judgments, overturned a Bombay high court verdict endorsing a trial court decision that cognisance of PC Act charges could not be taken against ex-chief Ramesh Gelli and ex-MD Sridhar Subasri of the erstwhile Global Trust Bank (GTB) in a Rs 41-crore corruption case because they were not public servants.

This was before GTB merged with Oriental Bank of Commerce (OBC) in 2004.

The CBI had lodged an FIR against Gelli and Subasri based on a complaint filed by the OBC’s chief vigilance officer. The charges of corruption and siphoning off Rs 41 crore date back to the time when GTB operated as a private bank.

Justice Pant said merely because the legislature had said that Section 46A of Banking Regulation Act was applicable only with respect to Indian Penal Code offences, operation of PC Act for the same offences could not be shut out.

“It is clear that object of enactment of Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 was to make the anti-corruption law more effective and widen its coverage,” he said.

Agreeing with Justice Pant’s conclusion that Gelli and Subasri should be prosecuted under PC Act as well, Justice Gogoi said, “In a situation where the legislative intent behind enactment of PC Act was to expand the definition of public servant, the omission to incorporate the relevant provisions of PC Act in Section 46A of the Banking Regulation Act can be construed to be wholly unintended legislative omission which the court can fill up by a process of interpretation.”

In doing this inclusive interpretation, Justice Gogoi said he was aware of the principle that what had not been provided for in the statute could not be inserted by the courts.

“Enactment of PC Act with the clear intent to widen the definition of ‘public servant’ cannot be allowed to have the opposite effect by expressing judicial helplessness to rectify or fill up what is a clear omission in Section 46A of the Banking Regulation Act,” he said. However, Justice Gogoi clarified that the judgment was not meant to obliterate all distinction between the holder of a private office and a public office.

“It will be more reasonable to understand the expression ‘public servant’ by reference to the office and the duties performed in connection therewith to be of a public character,” he said.

Before the amendment to Section 46A of Banking Regulation Act in 1994, only the chairman, director and auditor of a bank were regarded as public servants in connection with offences under IPC. But the amendment brought within its purview chairman appointed on a whole-time basis, managing director, director, auditor, liquidator, manager and any other employee of a banking company, terming them as public servants for offences under IPC.

The court ruled that if they were public servants in connection with offences under IPC, they would be deemed to be so under Prevention of Corruption Act as well.

“The unequivocal legislative intent to widen the definition of ‘public servant’ by enacting PC Act cannot be allowed to be defeated by interpreting and understanding the omission in Section 46A of the BR Act to be incapable of being filled up by the court,” Justice Gogoi said.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA